The Origins of the Scavenger’s Daughter

Among the infamous instruments of Tudor cruelty, few are as paradoxical as the Scavenger’s Daughter. To modern ears, the name sounds almost poetic — yet it belonged to one of the most merciless English torture devices of the 16th century.

Invented during the reign of Henry VIII by Sir Leonard Skevington — sometimes spelled Skeffington — the device was a perverse twin to the rack. Where the rack stretched the body toward dislocation, the Scavenger’s Daughter crushed it into silence.

To understand what the Scavenger’s Daughter is, one must look into the dark geometry of Tudor punishment. It emerged within a monarchy obsessed with loyalty, heresy, and confession — a court where justice was a spectacle and obedience was measured in endurance. The rack symbolized expansion through pain; its metal sinews echoed authority uncoiling. The Scavenger’s Daughter, by contrast, represented restraint — an inward implosion of flesh, faith, and fear.

The Mechanics of Pain: How Did the Scavenger’s Daughter Work?

So how did the Scavenger’s Daughter work — and why did it terrify even those who had never seen it?

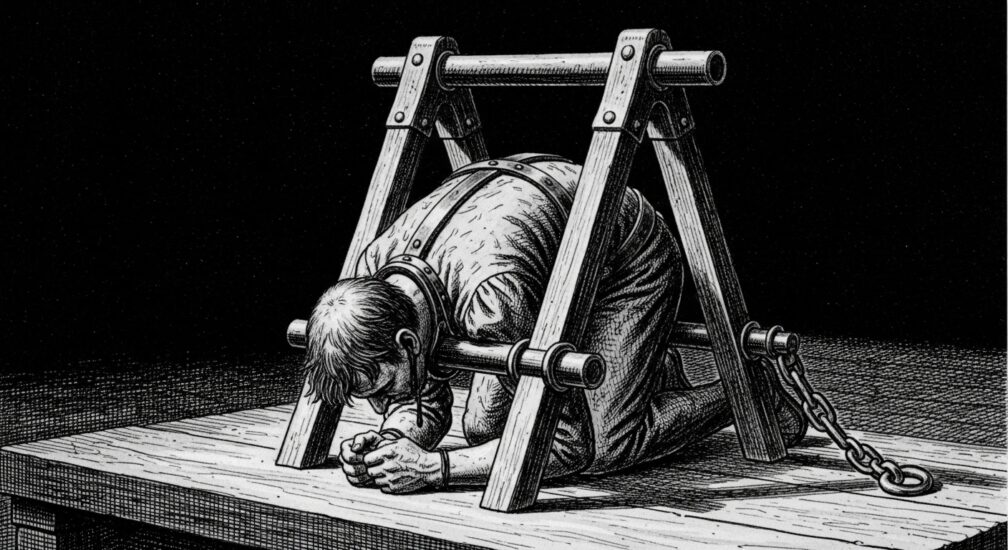

This device of mechanical cruelty was a hinged metal frame, roughly in the shape of a triangle or the Greek letter A. The prisoner was forced to kneel; the head was pressed down, the legs drawn up, and iron arms clasped around the back until the victim’s body folded upon itself. Blood surged from the nose and ears, veins bulged, and the body became its own instrument of torment.

Historians debate how did the Scavenger’s Daughter torture work in practice, yet accounts agree that it inflicted agony through compression rather than tearing. It was used sparingly — perhaps because it risked swift unconsciousness, or even death before confession. The Scavenger’s Daughter use therefore reveals a grim calculus: the pain had to be prolonged, yet productive. Its mechanism turned human endurance into evidence of guilt, bending the body as proof of sin.

Forged of iron and chain, this artifact became the inverse of the rack — a dark mirror of invention, where confinement itself was a language of oppression.

Torture in the Tower of London

The Scavenger’s Daughter lived within the stone walls of the Tower of London, where torture in the Tower of London served both as punishment and political theatre. These Tower of London torture devices were not simply tools — they were statements of authority, instruments through which the Crown sought to discipline both body and belief.

Inside those damp chambers, between flickering torches and whispers of confession, a prisoner might first face the rack, then the press of the Daughter, then interrogation by candlelight. To resist was to defy divine order; to confess was to justify one’s suffering. Silence, paradoxically, became both guilt and faith.

Every click of the screw echoed the machinery of Tudor justice — where monarchy, fear, and retribution coexisted in uneasy harmony.

Meaning and Cultural Legacy

In the centuries that followed, the Scavenger’s Daughter became more than an instrument of pain; it became a symbol of a medieval punishment system that confused justice with coercion.

The Scavenger’s Daughter meaning lies not only in its metal but in its philosophy: a belief that truth could be crushed out of the human form. In Tudor chronicles and later history, the device appears as both relic and warning — proof of how devotion to divine authority could twist into brutality.

Its legacy endures in the Scavenger’s Daughter history, reminding us that the quest for purity and control often yields anguish, not order. It stands beside the rack as the other half of England’s mechanical conscience: one stretching the body to its breaking point, the other folding it into submission.

From Dungeon to Museum Exhibit

Today, the Scavenger’s Daughter survives not in dungeons but behind glass — as a relic of human contradiction. At the Medieval Torture Museum in Chicago, visitors encounter reconstructions that challenge our understanding of justice and cruelty, evoking the fragile boundary between suffering and belief.

At the Medieval Torture Museum in Los Angeles, the display invites reflection on endurance and the limits of the body, showing how the will to dominate was engineered in iron and silence.

And at the Medieval Torture Museum in St Augustine, the Scavenger’s Daughter stands among other English torture devices, reconstructed with careful authenticity — each artifact a dialogue between past pain and modern empathy.

Those seeking deeper historical context can visit the museum’s blog, where essays explore English torture devices 16th century, moral philosophy, and the shadows that still shape our sense of justice.

Reflection: The Iron Paradox of Justice

In the end, the Scavenger’s Daughter embodies the paradox of a civilization that sought purity through punishment. Its cold metal frame compressed not only bodies but also the contradictions of its age — faith against reason, mercy against control.

The Scavenger’s Daughter medieval punishment reminds us that cruelty often wore the mask of righteousness. To study its history is to face the unsettling truth that beneath the rhetoric of order and confession lay the silent weight of human suffering.

Even as centuries pass, the image of that folded figure — bound in vice, bowed under guilt, yet enduring in silence — lingers as a symbol of the eternal struggle between oppression and justice, fear and faith.